The Economics of Labour: Robin Murray, Industrial Strategy and the Popular Planning Unit

By Hilary Wainwright

The idea of being ‘in and against the state’ [1] was the only way the five of us who joined Robin Murray in 1982 to form the GLC’s Economic Policy Group could make sense of becoming simultaneously both GLC ‘officers’ up against hostile administrative institutions and also socialist economic advisors employed to turn the GLC into an animator, resource and platform, supporting Londoners’ struggles to defend and create decent jobs, resist inequalities, and build convivial, sustainable communities.[2]

I had seen the importance of participatory forms of democracy and shared leadership through researching the formation of workers’ combines and had been inspired, like many other people, by Lucas Aerospace workers’ emphasis upon production for social need. Moreover, socialist feminists had been questioning the scope of the alternative economic plans on the left. They were saying that services for people – physical and emotional care – were activities which needed to be considered as well as the making of things. Extending democracy and creating jobs that served needs thus came together with us into the GLC.

The Popular Planning Unit, which I co-ordinated as part of the Economic Policy Group accountable to the Industry and Employment Committee (IEC), was one of many bridges linking the ‘In’ and the ‘Against’. While it was more of a rope bridge than one constructed with girders, we recognised the importance of the link. Most of us came from extra-parliamentary social movements, but we made our bridge function flexibly with spaces for inventive practice, which could also be gaps through which one might fall; precarious to walk across but with the advantage that only the nimble could follow – we were almost self-governing. Not always comfortable for those wanting a quiet life, but enjoyably tense for all with a liking for adventure.

The Popular Planning Unit in place and in practice

Moreover, we – all 15 or so of us (we kept growing, with new recruits for new tasks, interns, nomads from other parts of the GLC) - were indeed physically separate from the main building of the Council. We were in ‘the showroom’: a glass-walled building on Westminster Bridge, originally created, or so it seemed, from the glossy posters and leaflets left over from the previous Conservative regime proudly showing London at the bottom of the scale of international wage rates – to advertise London as a city in which to invest.

From this office we both worked with Londoners organising in workplaces and in communities to defend their jobs or to campaign and sometimes to create new ones, and also we prepared proposals to the Industry and Employment Committee (the GLC committee responsible for our budget) recommending that the GLC fund and politically collaborate with many of these organisations and initiatives as part of developing its London Industrial Strategy, through ‘doing’ at the same time as researching. The most important part, then, of our activities ‘in’ the state was our negotiation around these proposals with the finance and legal departments of the GLC and our presentation of them as papers to the I&E Committee.[3]

A day in the life of a popular planner might consequently consist of meeting with shop stewards facing factory closure in the morning, then a quick lunch to report back to Robin Murray and a researcher on the relevant sector, before returning to the PPU to prepare to present a paper to committee. At 1.55, a male popular planner would grab the red tie that hung for all to use by the desk of John Hoyland, co-editor with Sheila Rowbotham of Jobs for a Change (our monthly newspaper), and run along a section of the 22 miles of GLC corridors to talk before the Committee assembled with senior legal and financial advisors to begin a long agenda at 2pm. (That red tie, seems in retrospect a symbol of the double life of a popular planner being ‘in’ as well as ‘against’ the GLC – and we women found our own speedy ways of ‘dressing for committee’).

The evening might consist of a drive to the Royal Docks to sit in on the campaign against the STOL port (the Short Take Off and Landing Airport which, after a strong campaign and a sceptical public inquiry, became City Airport – largely because the Thatcher government had abolished all local planning powers and introduced the London Docklands Development Committee to turn Docklands into a dormitory and infrastructure extension of the City of London). PPU’s role in the meeting of the campaign against the airport was mainly to listen and discuss how the GLC could help.

So what did all this varied activity have to do with developing an Industrial Strategy for London, and what made it innovative and threatening to the conservative establishment both in County Hall and across the Thames in Westminster and Whitehall?

Popular Planning, the London Industrial Strategy and the transformation of production

This seemingly uncontroversial process of a group of elected representatives – the majority of whom were Labour councillors – agreeing to share public funds and hence public power with citizens working to defend or create employment, was in fact part of a radically democratic approach to an economic policy that had at its centre the transformation of production. Moreover, the institutional innovations involved in this process were vital to the way that Livingstone’s GLC and Popular Planning, most strikingly, broke from the traditional, hierarchical and centralised forms of public administration inherited from the Second World War and consolidated by Clement Attlee’s 1945 Labour Government. The work of PPU and more generally the Economic Policy Group exemplified – with all the messy, unevenness of an experiment in progress – a move towards open, power-sharing and devolving forms of administration: a new form of public administration that would later be brilliantly theorised by Robin.[4]

Up until the experience of the GLC’s London Industrial Strategy, the conventional choice for employment policy was either jobs created by public institutions, different branches of the state, or jobs created through the private market, sometimes with support from the state.

Our proposals to the IEC, often leading to contributions to the London Industrial Strategy, came from a very different tradition of economic thinking, one that emphasised production as a site of transformation. This focus on production involved an approach to economic problems, especially employment, that required an interventionist state, but a state that intervened in production and the relationships and values shaping production. Robin in his introduction to the strategy explained the importance of this shift: “The growth of unemployment, and unmet need, the decline of private industries and public services – all indicate a deep failure of policies (whether Monetarist or Keynesian) based on adjusting the market. What is required is a change in direction in economic strategy, towards direct intervention in production.”[5]

The idea however was not a purely economic shift, from one sphere of the economy to another, it was also a change in the purpose of economic activity, the balance of power, the values and character of social relations underlying the control of production and the direction of its transformation. Once we challenge the priorities of the financial markets, there are definite, effectively political, choices to be made between alternatives. Robin’s voice in the introduction to the London Industrial Strategy is very clear and firm on this: “At the moment, overriding priority is given to private market production and to the military sector, to increased intensity of work within the factory, and the technological replacement of awkward labour. We call this militarised market production. It represents the economics of capital. There is an alternative which we call socially useful production, which takes as its starting point not the priorities of the balance sheet, but the provision of work for all who wish it in jobs that are geared to meeting social need. William Morris referred to it as useful work rather than useful toil. It represents the economics of labour.”[6]

Popular planning equals sharing power

Such a transformation of the relations and institutions of production could not be achieved by the state alone, ‘intervening’ from above with the expertise of the planner. “Normally,” argues Robin in the London Industrial Strategy, “the resources and the powers to plan have remained at the centre within the state or shared with management. Worker or community involvement has taken on a secondary, consultative form, commenting on plans drawn up within the public authority. Popular planning by contrast, involves sharing power [my emphasis], empowering those without official power. The end result on many occasions, for instance the People’s Plans in Docklands and in Coin Street, the campaigns against hospital closures, and the alternative plan at Ramparts Engineering is an alliance around policies worked out together. Such alliances allow more power than either the GLC or the trade union and community groups would have on their own.”

One of the best examples of cultural campaigning and collaboration in the 1980’s funded by the GLC. See the work of www.cspace.org.uk/ and www.arte-ofchange.com. All photos © Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Docklands Community Poster Project, 1984

The first People’s Armada arrives at Parliament. Over a thousand people from the London Docklands sailed up river to protest against the way the area was being re-developed and to deliver the People’s Charter for Docklands to Members of Parliament.

Some of the vessels participating the second People’s Armada. Three People’s Armadas to Parliament took place from 1984 to 1986.

Dragon Banner. Fabric banner featuring a dragon in the shape of the River Thames that became a symbol of the Docklands fightback. Used on the lead barge during the People’s Armadas to Parliament.

Changes in the purpose, relations and processes of production required the interventionist local state to have a close alliance with the creative forces on which production depends, i.e labour of all kinds, in manufacturing production, in cultural production and also in domestic production and the relationships involved in creating and reproducing a community. Every section of the strategy has detailed discussion of the alliances possible in each sector to change the balance of forces in favour of labour and the creation of useful jobs to meet social needs.

A strategy not a plan

In that sense it was important, paradoxically, to the work of the Popular Planning Unit that the London Industrial Strategy was a strategy and not a plan. A strategy implies, in Robin’s terms, “conflict, limited resources, and a ground level perspective which was always having to guess what was over the horizon”. “What it implied in practice”, he continued, “was a view of the London economy as composed of innumerable battlegrounds, involving a struggle for jobs against the pressures of the market... each case was fought over a particular terrain, with its specific balance of forces – of local communities, workforces, perhaps the support of a borough council in one case, of a local resource centre in another. Each case required its own strategy, geared at first to the immediate terrain.” Robin contrasted this to a plan, which implies “a blueprint, drawn up from above. The London economy was too complex, the powers of the GLC too limited, the knowledge of the planners too narrow for this ‘railway timetable’ model of public intervention to be relevant for the GLC.”

The knowledge of those who joined the PPU was exactly the knowledge of the ground terrain, and of the different sources of power which become apparent in the course of struggles on this terrain. Much of such knowledge is practical – and often tacit – though it can be helpfully combined with knowledge about underlying trends shaping what action is possible; knowledge that is beyond what can be known through direct experience or tacit hunches or understandings and requires research of an historical or statistical kind. The Economic Policy Group, under Robin’s leadership, brought together different kinds of knowledge and indeed valued the combination and interaction of these different forms – a distinctive feature of his thinking and leadership, shaped especially by his work on the labour process carried out through theory and a close observation of practice as part of a course on Marxism that he led at Sussex University with Mary Kaldor.[7]

The politics of knowledge: the sharing of practical knowledge

What Popular Planners shared was a background of organising that was about recognising, valuing and sharing practical knowledge; knowledge that the free-market right treated as exclusively that of ‘entrepreneurs’, to be organised through the market, and knowledge that social democrats have traditionally ignored in favour of the kind of codified statistical knowledge that can be centralised through the state.[8] By contrast, the PPU members, before joining the unit, had helped workers and communities in different ways to share and collectivise their practical knowledge, including of immediate sources of power. For example, Alan Hayling had worked at Ford and helped to organise the Ford workers’ combine committee to resist the mass production line; his understanding of the struggle at Ford was vital to the GLC’s ability to support the international co-ordination of Ford workers and the public hearings organised by the GLC to expose and scrutinise Ford’s strategy for production in Europe, that led to the closure of production in Dagenham. Or Richard Hallett, who had worked in a research and resource centre in Coventry to support workers sharing their knowledge through their own workplace and city-wide organisations and drawing on the centre’s research to produce alternative plans to company plans for ‘restructuring’ and redundancies. He was able to work with the unions in British Telecom to publicise their alternatives to privatisation and expose to public criticism the inefficiencies of privatisation for the people of London. Dave Welsh had worked as a guard on the Underground and been active in campaigns against one-person operated trains on the basis of workers’ knowledge that this was unsafe. Sheila Rowbotham joined us with her deep understanding and experience of the women’s liberation movement, and its ways of organising to prefigure the emancipation they were working towards.

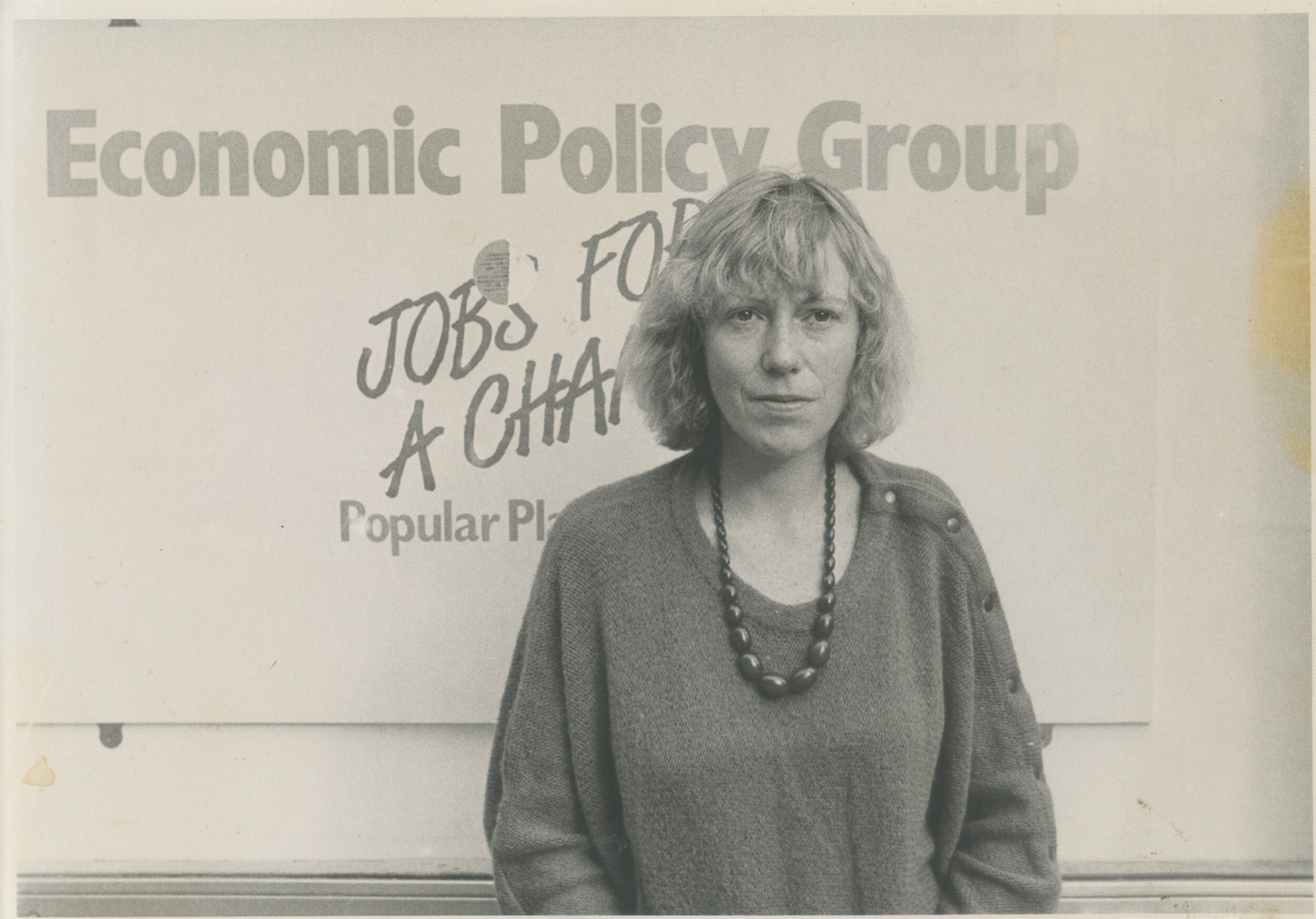

Sheila Rowbotham, co-editor with John Hoyland, Jobs for a Change newspaper, GLC 1986

Indeed, all those who worked for the Popular Planning Unit – and also its allied institutions of the IEC, most notably the Technology Networks supported by the Greater London Enterprise Board and the grant-giving team of the Project Development Unit, shared a commitment to the dignity and capacities of working people and to strategic work for a form of economic and state organisation that would realise these capacities for the benefit of all.

Peoples Plan Centre: grassroots planners for Docklands funded by the GLC

Workplace Nursery funded by Industry and Employment, GLC

Newham Unemployed Centre funded by Industry and Employment, GLC

Brent Black Music Training project funded by Industry and Employment, GLC

A group of women who campaigned to keep their public wash house open in the mid 1970s eventually formed a community laundrette under the Westway. This was funded by the Industry and Employment team at the GLC and eventually the Greater London Enterprise Board introduced Combined Heat and Power to reduce the energy used in the driers. The women using it did the washing for the nursery next door which was funded by the GLC Women’s Committee.

The generation of 1968 and its brief taste of power

This convergence of staff with a common political ethic – though in different political organisations or (more likely) none – was more than a haphazard result of the GLC’s recruitment process, and points to a feature of the distinctive historical context of what became known as ‘the Livingstone GLC’.

The early 1980s were an important moment in the transition from the post-war settlement – with its macro-economic conditions of full employment, standardised welfare provision to meet basic needs and its virtuous circle (as it seemed at the time) of mass production compensated with high wages to sustain mass consumption. This was a transition over which a political struggle had been taking place since the early 70s, between the economically militant trade union shop floor activist base and a radicalising Labour party, facing corporations under competitive pressure and a Tory party abandoning its allegiance to the post-war consensus and attracted by an outright attack on both the welfare state and trade union rights. In this context, and as if history took a knight’s move, a generation was coming to maturity that had been shaped by the movements of 1968, which inspired anti-authoritarian rebellions on an international scale in favour of a democratic, humanistic alternative to the centralised, commandist bureaucracies of the post-war order, in the private and the public sector alike.[9][10]

It was writers, educators and organisers from these movements who constituted the Popular Planning Unit. Instinctively as our work got underway we organised together on the principles of the movements of which we had all been part. The convergence of thought and practice was obvious at our weekly meetings, away from our desks around the relaxed seating area of the showroom (‘California’, as we were sometimes called, with a note of restrained envy, by other parts of the Economic Policy Groups, imprisoned in the desk-dominated space of County Hall). Whether from the shop stewards’ movement, the women’s movement, the tenants’ movement [11], the peace movement, networks of activist researchers or the black and anti-racist movement, several principles were taken for granted:

First, a shared rejection of an instrumental method – of the ‘ends justifying the means’ – and instead the search for ways of organising which were consistent with the values of the society we were working for. Hence, equality, inclusiveness and mutual care were all important.

We broke down the hierarchy of County Hall as far as we could in our own organisation, even if we had to deal with it as an unavoidable part of gaining the resources of the Industry and Employment Committee for the projects on which we worked with activist Londoners. We rotated the chair of the meetings; administrative and secretarial staff in PPU were full members of the team; care was taken to ensure that all voices were heard and that everyone was supported if they were facing difficulties.

Openness and transparency were important principles, not only internally and with other members of the Economic Policy Group.

Making policy and implementing policy were closely aligned. All our work was implementing some commitment or other of Labour’s employment manifesto while also supporting Londoners to shape the London Industrial Strategy.

One of our principles of working was to involve the users of a service, or the community surrounding a factory, as well as the workers.

In this process, we saw our relationship to the London citizens with whom we worked as facilitative, educational and animating rather than ‘delivering’.

Looking back, and reflecting on the experience with the benefit of Robin’s writings on public administration in the early 1990s, we were answering his central challenge: as to “whether there are forms of public administration which, without resource to the market and its limits, can move beyond the mechanical model (evident in the hierarchies and division of labour of Fordist forms) to provide the basis of the flexible state”.[12]

In practice, we – and other new units of Livingstone’s GLC – were exemplifying some of the basic social relations of an open, flexible and deeply democratic form of public administration in which public servants were serving the public, supporting civil society, not simply commanding an apparatus on behalf of the representatives of the public. For four years, Londoners were served not by ‘public officials’ but by ‘civil civil servants’ as Robin used to describe us all, himself included.

But we weren’t able to sustain and reproduce these changed relationship in order to transform them into the basis of new institutions. It was partly the abolition of the GLC which prevented an experiment from being tested as the basis of enduring institutions, but it was also the wider incompletely resolved problems that our experiment generated. Problems of co-ordination and integration with the Economic Policy Group (or rather ‘the Industry and Employment Directorate’ that it had become due to its growing size and the reach of its policy). This was, in other words, the problem of how a diverse and autonomous network of actors pursue shared goals in the interests of maximising public benefit. There were problems too of the limits of representative democracy, the limits of the separation of policy and implementation implied by the periodic, five-yearly cycle of the vote – a minimal form of popular democratic engagement- without any more direct mechanism for enlivening the democratic mandate or organising popular participation in its implementation. These latter issues of representative democracy also raise challenges for the conventional party form, organised around exactly the separation of policy and implementation – the party develops the policies for its representatives to implement when elected to government (without any further engagement by the party, let alone its non-parliamentary supporters).

These challenges and many more are all raised by our relatively brief, albeit intense, experience/experiment of the Livingstone GLC in general and the Popular Planning Unit in particular. They require further work and more practical experiences/experiments before enduring institutions can emerge. But one lesson of lasting significance is clear and that is the importance for the new relations we created of consciousness and understanding, particularly as it pertained to the consciousness of being a servant of the people in a new way, whether as a public employee or manager, or as a political organiser or writer/researcher. One of the conditions of success of the PPU and indeed the EPG as a whole was the transformative social education so many of us had received through the social movements of the late 60s and 70s; moreover the personal and political perspective of Robin, and of Mike Ward, was also influenced by these movements. Also important was the ways in which those GLC public administrators, notably Pam Gordon and Trevor Richardson who facilitated our work, combined a close understanding of new policies, processes and people with an appreciation of our innovative , albeit unconventional, attempts to open up the GLC’s resources to the public alongside an understanding of the constraints of fiduciary duty within which we legally needed to work.

For me, the lesson here is that new kinds of state institutions and relationships require new kinds of ‘civil civil servants’, including those who sometimes will have to work in and against the state. And for this we need as a matter of urgency a new educational organisation, probably of a decentralised kind, to train such people. A possible project for many readers of this website to work on together? The Robin Murray Network for Civil Civil Servants? Education for a new kind of state. It was an idea, or the seeds of an idea, about which Robin often mused. Can we make it a reality?

August 2020

REFERENCES

[1] See London Edinburgh Weekend Return Group 1979, ’In and Against the State’ Pluto Press, London

[2] For more information see ‘The GLC story’.

[3] These negotiations were an interesting experience for Popular Planners used to working in collectives and in movements; we later heard that many of the finance and legal officers also enjoyed the experience of a closer encounter with policies directly involving fellow citizens – we found we could make allies amongst senior officials who appreciated the new sense of purpose and innovation that Livingstone and many of the new units brought to the GLC. Often, it connected them with the very reason why they chose to work with the public sector. For example, when Mr Fitzpatrick, the head of legal, responded to my request for his say-so for a committee paper recommending tens of thousands of pounds be spent on our programme of economic literacy, he ended up recalling his time as a Scout Master as he agreed that such a programme of popular education would be in ‘the interests of all or some of the people of London’ (the vital legal provision in the Local Government Act with which our proposals had to comply).

[4] See Robin Murray, “Introduction”, in Robin Murray (ed.) New Forms of Public Administration, IDS Bulletin, vol. 23, no. 4, 1992 and Robin Murray, “Towards a Flexible State”, in Robin Murray (ed.) New Forms of Public Administration, IDS Bulletin vol. 23, no. 4, 1992.

[5] Page 17 of the Introduction to the London Industrial Strategy, para 1.51

[6] Page 18 of the Introduction to the London Industrial Strategy, para 1.52

[7] See the Brighton Labour Process Group

[8] See Wainwright, Hilary, ‘A New Politics from the Left’, Polity. Cambridge 2018

[9]See Robin Murray, “The State after Henry”, in Marxism Today, pp 22-27, May 1991.

[10] See also Anthony Barnett ‘Out of the Belly of Hell: Covid -19 and the humanisation of globalisation’ Open Democracy. 21st May 2020

[11] Note about one of our members, Peta Sissions.

[12] Robin Murray (ed.) New Forms of Public Administration, IDS Bulletin, vol. 23, no. 4, 1992, page 85