Robin, a lodestone and lodestar.

I knew Robin Murray because I was at university with Frances, though I am unsure exactly when we met. However the first time I heard him speak was in Walthamstow, North East London during the late 1960s when he was connected with the May Day Manifesto Group. The ‘manifesto’ had appeared in 1967 and then expanded to become a Penguin the following year. It was a thoughtful attempt to launch a left socialist alternative to mainstream Labour which could be ‘ contemporary in experience, educated in method, democratic in organisation and strong in action.’ (p.189)

May Day was not to materialise as a national movement but many local community groups took off and I was aware of QueenSpark publishing in the 1970s in which Robin and Frances were involved.

It was to be through working at the Greater London Council from 1983 to 1986 that our paths crossed and connected. Robin headed the Industry and Employment Unit which was committed to developing an alternative economic strategy for London. Hilary Wainwright was running the Popular Planning Unit and the small band at the GLC was recognising they had to expand by the time I arrived.

Robin’s enthusiasm was infectious. Municipal economic planning might sound like a dry topic but he infused it with an heroic gusto. Robin traced economic threads way beyond London itself, linking up to miners in Wales, co-ops in Italy and shop stewards in Brazil.

We new arrivals were viewed by many of the seasoned workforce as a cross between a guerrilla invasion force and deranged visionaries. Robin remained totally un-phased, striding the corridors bearing an eclectic banner in which the Webbs nestled next to Abercrombie and Workers’ Control.

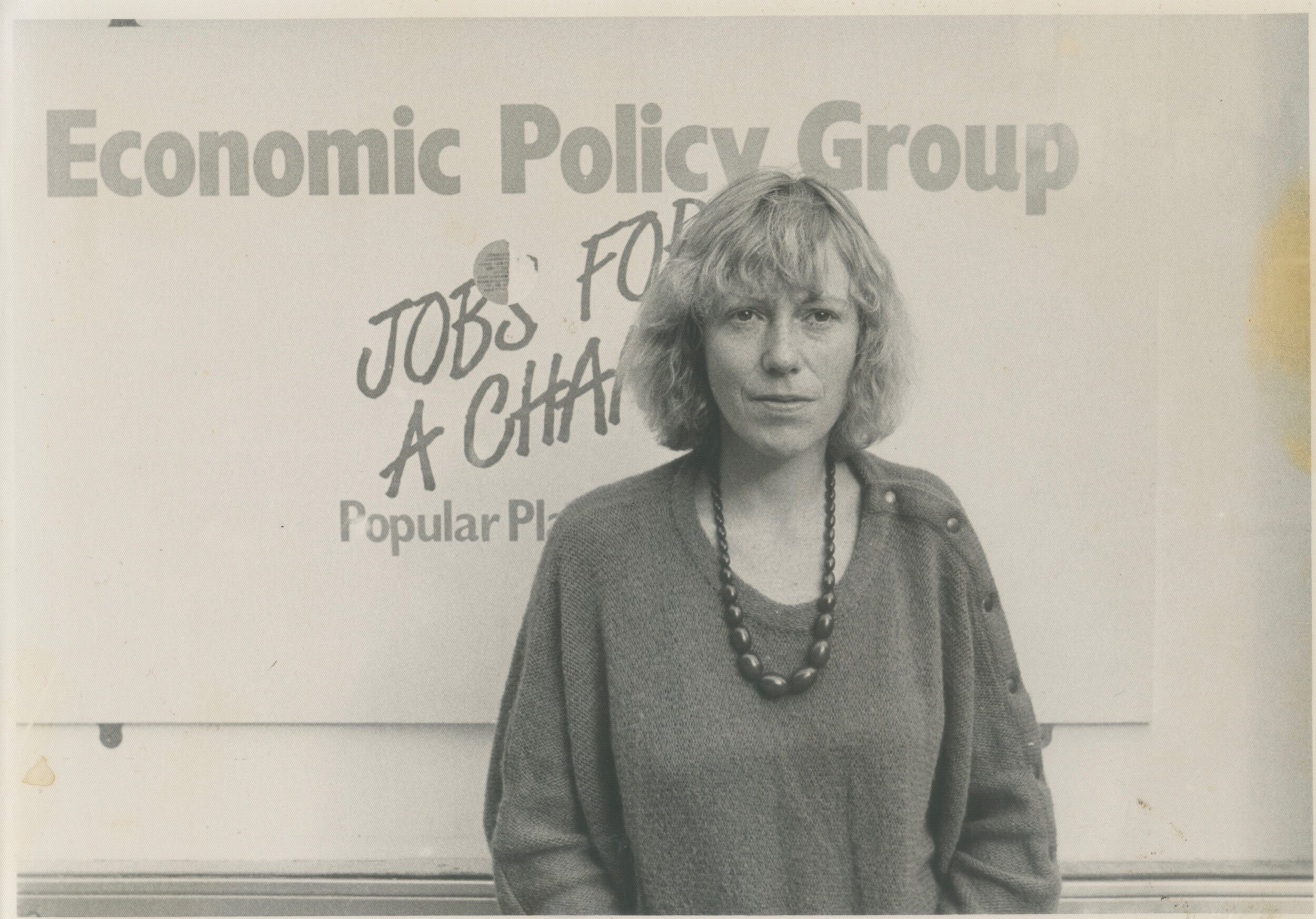

I soon found out that his idea of what an individual worker like me could accomplish were capacious indeed. After one meeting I went home realising I appeared to be co-editing the newspaper ‘Jobs for a Change’ as well as being responsible for integrating domestic labour and child care into the economic strategy, not to mention London’s cleaners and even dry cleaning businesses. I think the latter was because I mentioned being friendly with the Turkish Cypriots who ran the cleaners in Clapton. As I was only employed for three days a week because I had a six year old child, even Robin decided my job was not feasible. To my relief bits of my brief were shed.

Robin was so open to creative ideas that with the support of the Labour councillors we soon started not simply to expand the scope of economic strategy but to find diverse ways of involving Londoners, from music festivals to exhibitions.

GLC Committee meetings were a bizarre mix of the tension of horse racing and the fusty dusty style of a nineteenth century office. In contrast Robin defended new ways of writing about policies, causing the Conservative members to blink in surprise.

His calm confidence extended outwards, enabling us all to do more than we could have imagined was possible. His great skill lay in extending hegemonic power to others in a cooperative spirit.

He even affected the Conservative councillors who were meant to be in opposition. In 1986 when Margaret Thatcher’s government finally managed to abolish us, they thanked us profusely for all our work!

Regardless of Thatcher’s political vandalism, the friendships formed could not be abolished. Robin was a lodestone and a lodestar for me and I miss him.

Peoples Plan Centre: grassroots planners for Docklands funded by the GLC

Newham Unemployed Centre funded by Industry and Employment, GLC

A group of women who campaigned to keep their public wash house open in the mid 1970s eventually formed a community laundrette under the Westway. This was funded by the Industry and Employment team at the GLC and eventually the Greater London Enterprise Board introduced Combined Heat and Power to reduce the energy used in the driers. The women using it did the washing for the nursery next door which was funded by the GLC Women’s Committee.

Workplace Nursery funded by Industry and Employment, GLC

Brent Black Music Training project funded by Industry and Employment, GLC

Sheila Rowbotham, co-editor with John Hoyland, Jobs for a Change newspaper, GLC 1986