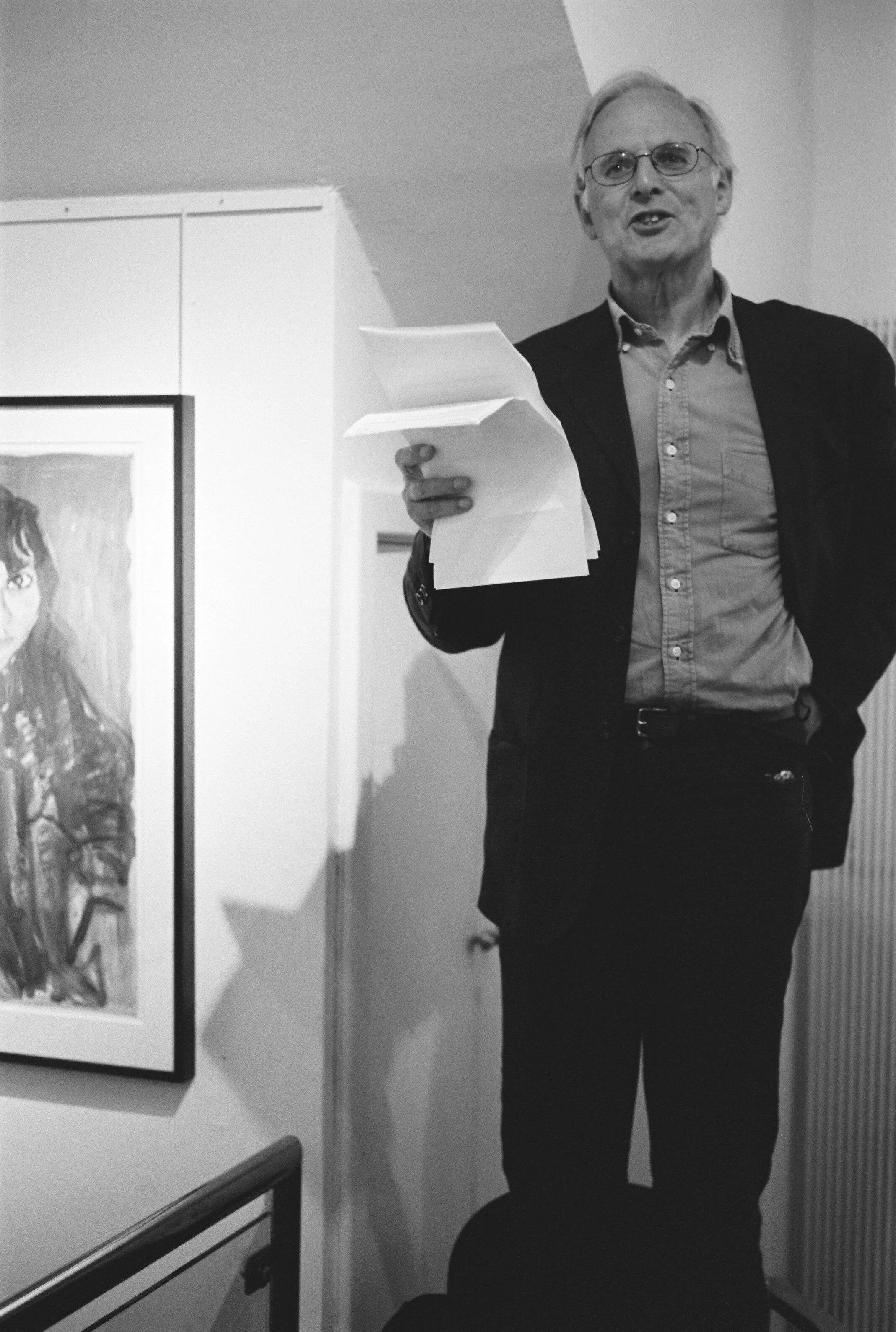

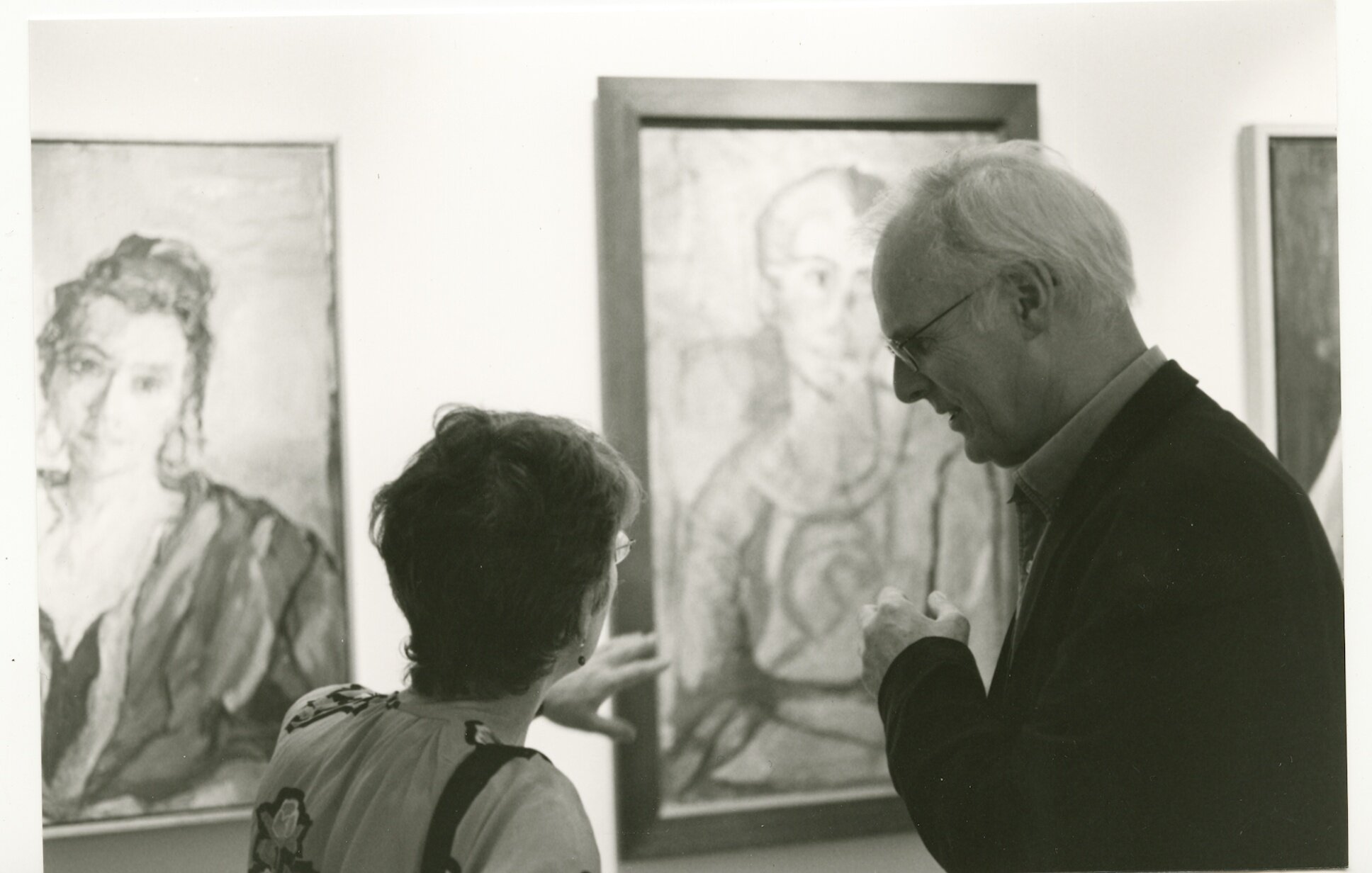

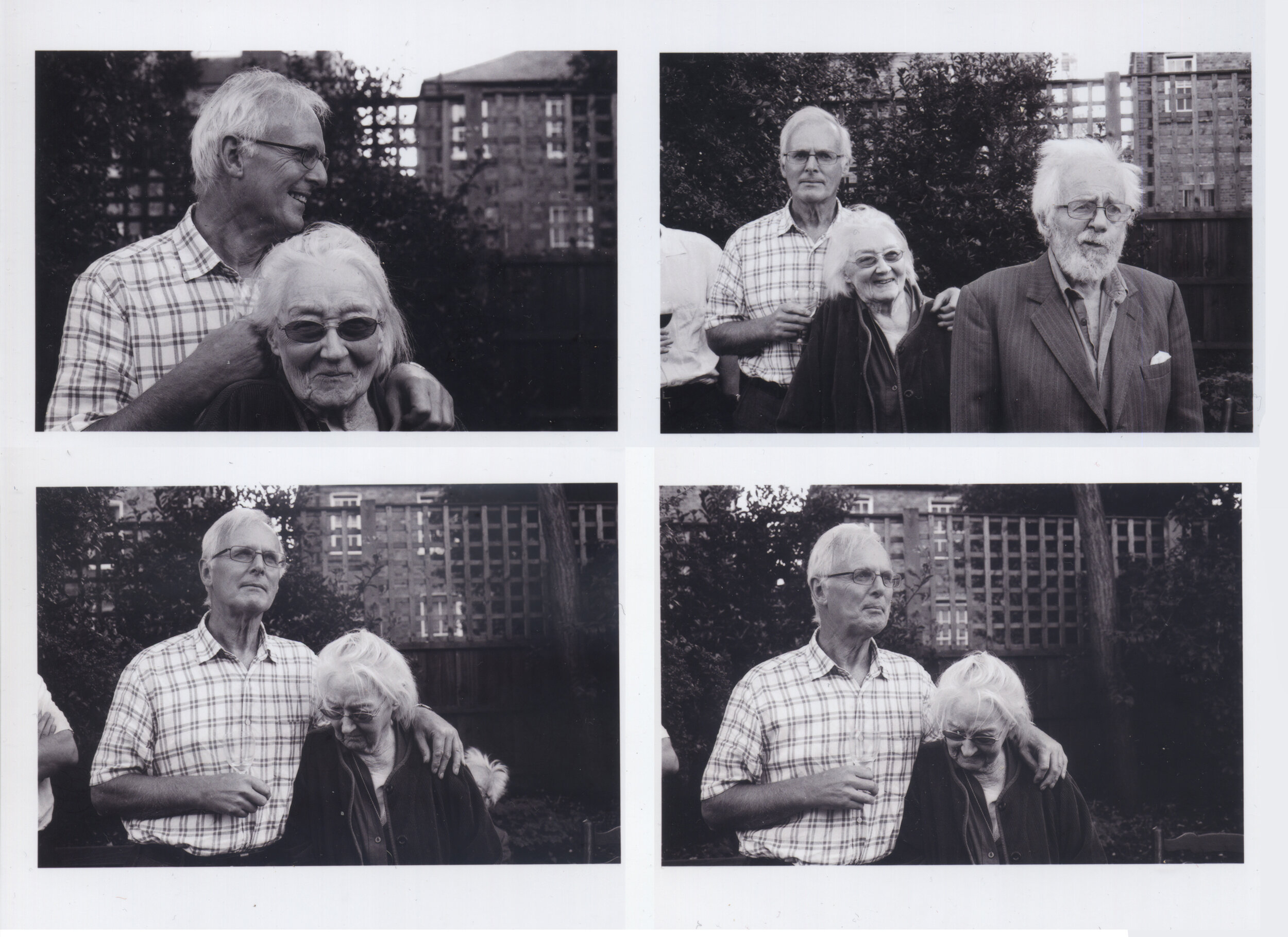

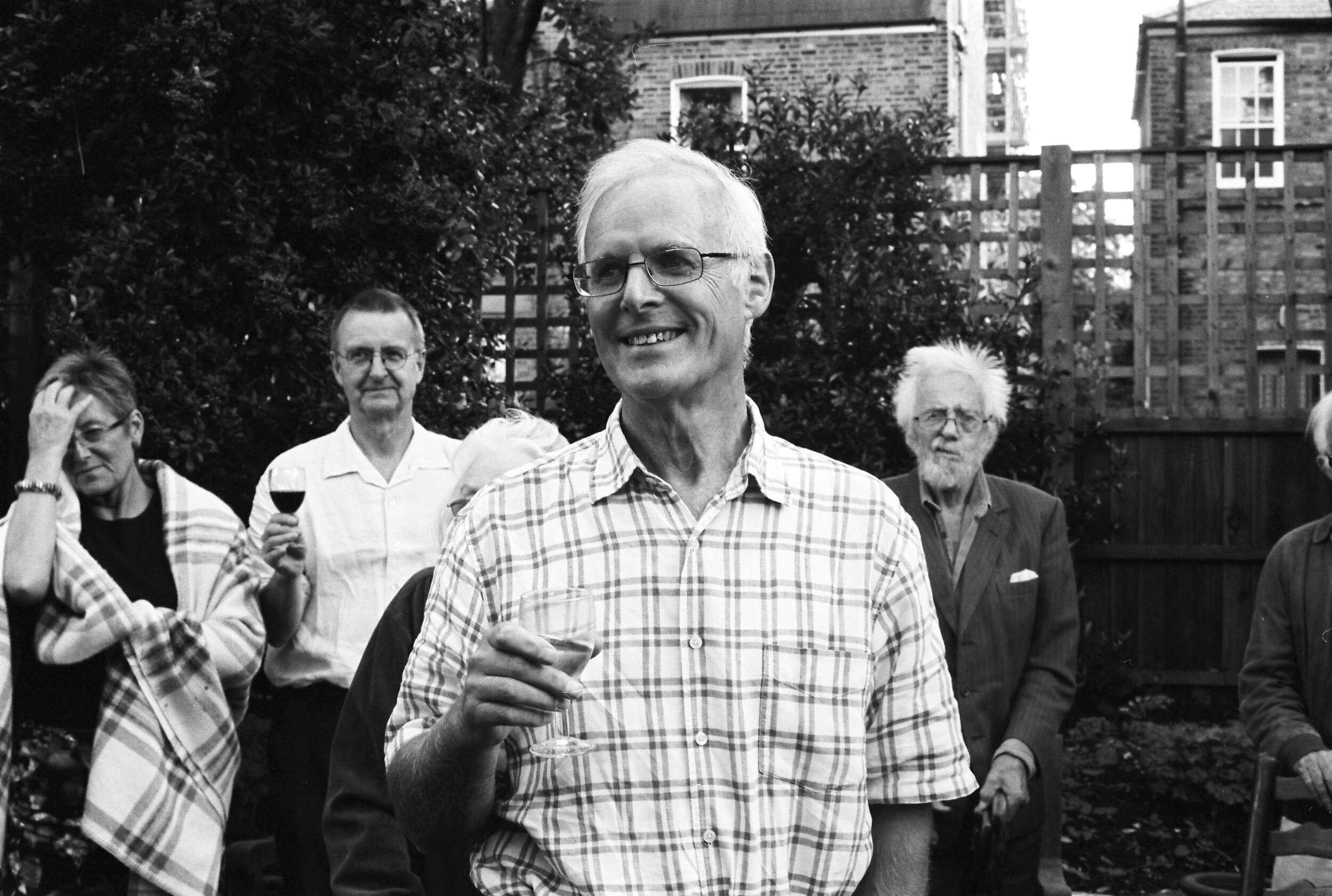

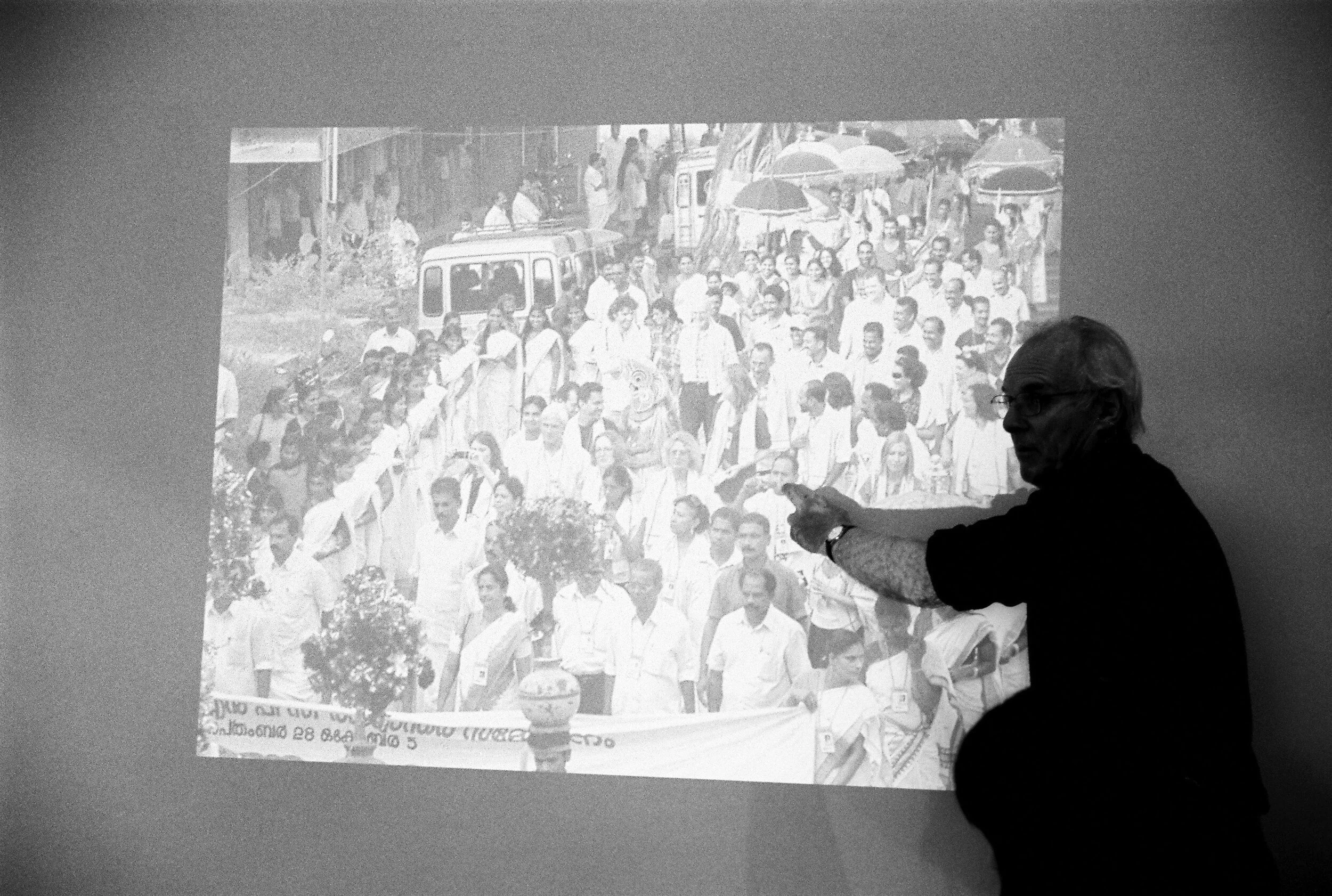

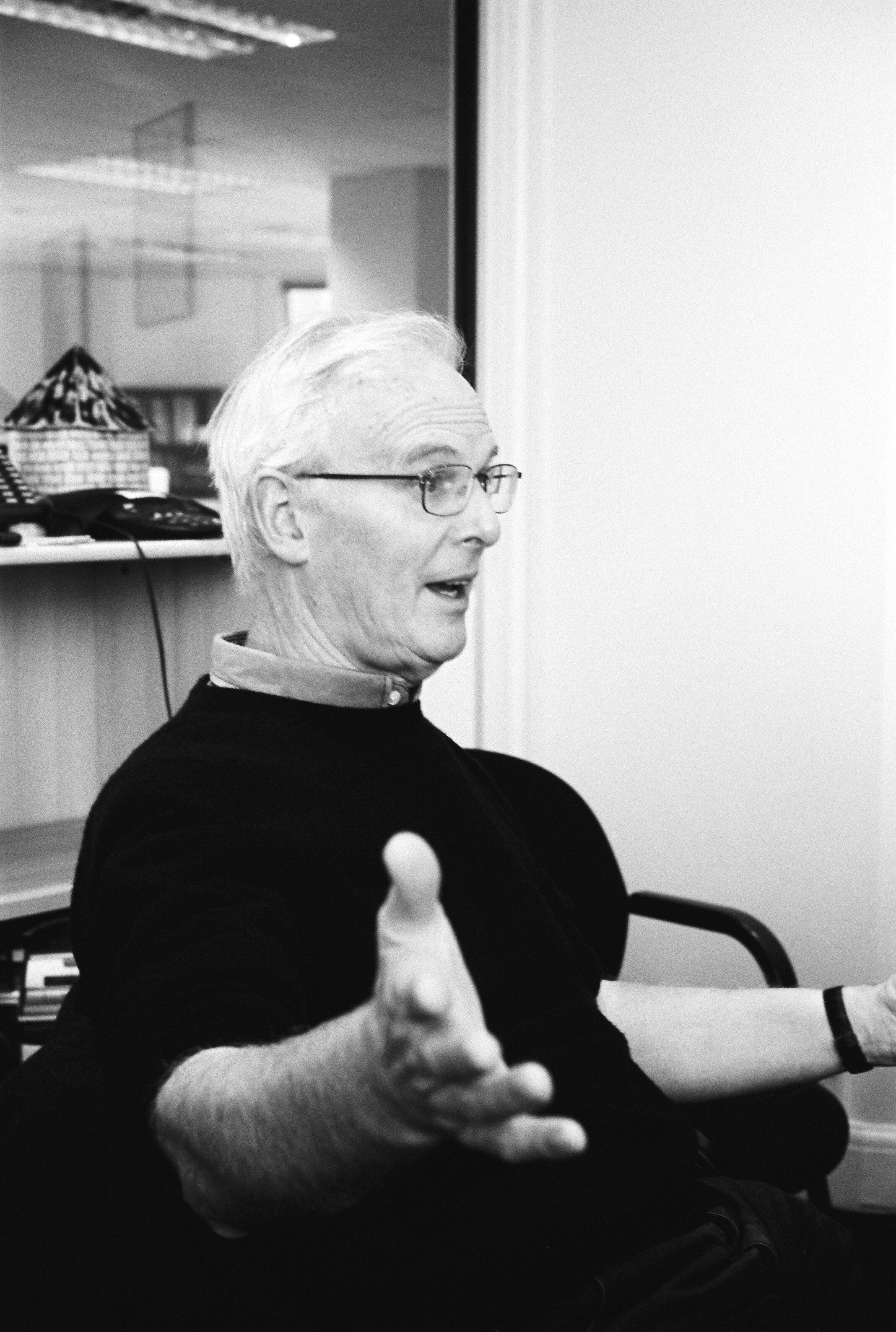

Robin Murray or the beauty of life, a photographic essay

This is the story, in images and words, of some special moments I shared with Robin from 1977 in Brighton until his death in 2017. Forty years of friendship, full of exciting projects, each new one more so than the last.

Such is the vigorous reach of Robin’s vitality and intelligence that in evoking the moments in which I worked closely with him and the projects we were involved in together, I often found myself using the present tense.

The Brighton years

I met Robin as soon as I arrived at the Institute of Development Studies (University of Sussex, Brighton) in 1977. He was very interested in the work I had just been doing in Angola. He was then preparing a seminar on development strategies for around thirty economic leaders from various Third World countries. This was to run for several weeks, of which one was dedicated to a role-play on Angola, with participants representing three opposing tendencies in the Central Committee of the MPLA — the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (Mouvement Populaire de Libération de l'Angola) — which had just taken over the reins of power: a pro-Western liberal tendency, a pro-Soviet tendency and a third, strictly nationalist one. Each of the three groups was to define and defend a development strategy for three key economic sectors of the country: oil, diamonds and coffee. For each participant, we prepared a file on these three sectors with numerical data, so that they could make the appropriate calculations.

The participants immersed themselves in this game, arguing rigorously about the economic and political benefits of their own proposals and the drawbacks of opposing strategies. In the case of oil, the confrontation centred on the respective advantages of a partnership with a multinational company, with the USSR or with Algeria. With regard to diamonds, the debate was whether, on the one hand, to continue collaborating with the South African De Beers in one of two potential ways, each with a different requirement with regard to royalties, or, on the other, to seek freedom from this domination by pursuing an alliance with the USSR. As far as coffee was concerned, the participants’ political orientations found expression in three radically different strategies: maintaining existing colonial properties in order to avoid a drop in production and quality; nationalising these properties for the benefit of public enterprises that would mobilise the population to take on jobs such as bringing in the harvest; or creating a multitude of small farms by redistributing the existing plantations among workers and peasants. After a week of intense debates chaired expertly by Robin, the participants all stressed how much the game had helped them to think through the various dimensions of a development strategy.

Robin lost no time in inviting me to join the Brighton Labour Process Group (BLPG), an informal group that reflected on issues connected with the process of work. It had published a kind of manifesto in the form of an article, ‘The capitalist labour process’, in the first issue of the review of the Conference of Socialist Economists, ‘Capital and Class’. Every Friday evening, we would either analyse the labour process in a particular sector, such as industry, agriculture, education, health, communication or national defence ... or flesh out a theoretical point. The minutes of these meetings, always written up by Robin, are treasure troves of reflection and questioning. They teem with new ideas, of which some were not even mentioned in our discussions. This experience was all the more rewarding because the group was multi-disciplinary and included such high-powered personalities as the economists Aboo Aumeeruddy, Fred Bienefeld, Diane Elson, Don Mather and Keith Smith, the philosophers John Mepham and Kate Soper, the historian Stephen Yeo, the weapons specialist Mary Kaldor, the anthropologist Caroline White and the businessman David Youlton ...

In this group, several of us were ‘dialectically United’ men: this was the name of our football team, in which David Youlton was a mainstay of the defence, Robin and John the midfield strategists and I the striker. There were three halves to the matches: first, the game, where we exultantly rolled out our tactics on the field, then the shower (during which endless discussions took place, for example, on the law of value, the fetishism of goods or the exploits of Manchester United, the football club that Robin had supported since his childhood) and, finally, the Pub, this convivial place where, as the British say, one feels at home. We played mainly with students and researchers from Latin America. A few years ago, when Robin was invited to Brazil for a conference on Industrial Strategies, the organiser of the gathering, realising that Robin did not recognise him, cried out, ‘Robin, don’t you remember? Dialectically United!’

The seminar on socialism in the Third World that Robin organised with funding from the British Government over six weeks in 1979 gave public sector officials and civil society representatives from the countries concerned (Ethiopia, Mauritius, Mozambique, Madagascar, Sri Lanka and Vietnam) as well as specialised researchers working on a range of countries (Cuba, Nicaragua, Peru, China, Cambodia, Vietnam, Algeria, Angola, Mauritius, Mozambique and Tanzania) the chance to debate and explore in depth questions around the forms of organisation used in certain key sectors, such as industry, agriculture, health and education. The discussions shed light on the gap between an authoritarian, statist conception of socialism and a democratic one based on cooperatives and associations, with an emphasis on social and economic innovation. In this context, the ideas developed by the Brighton Labour Process Group proved their value.

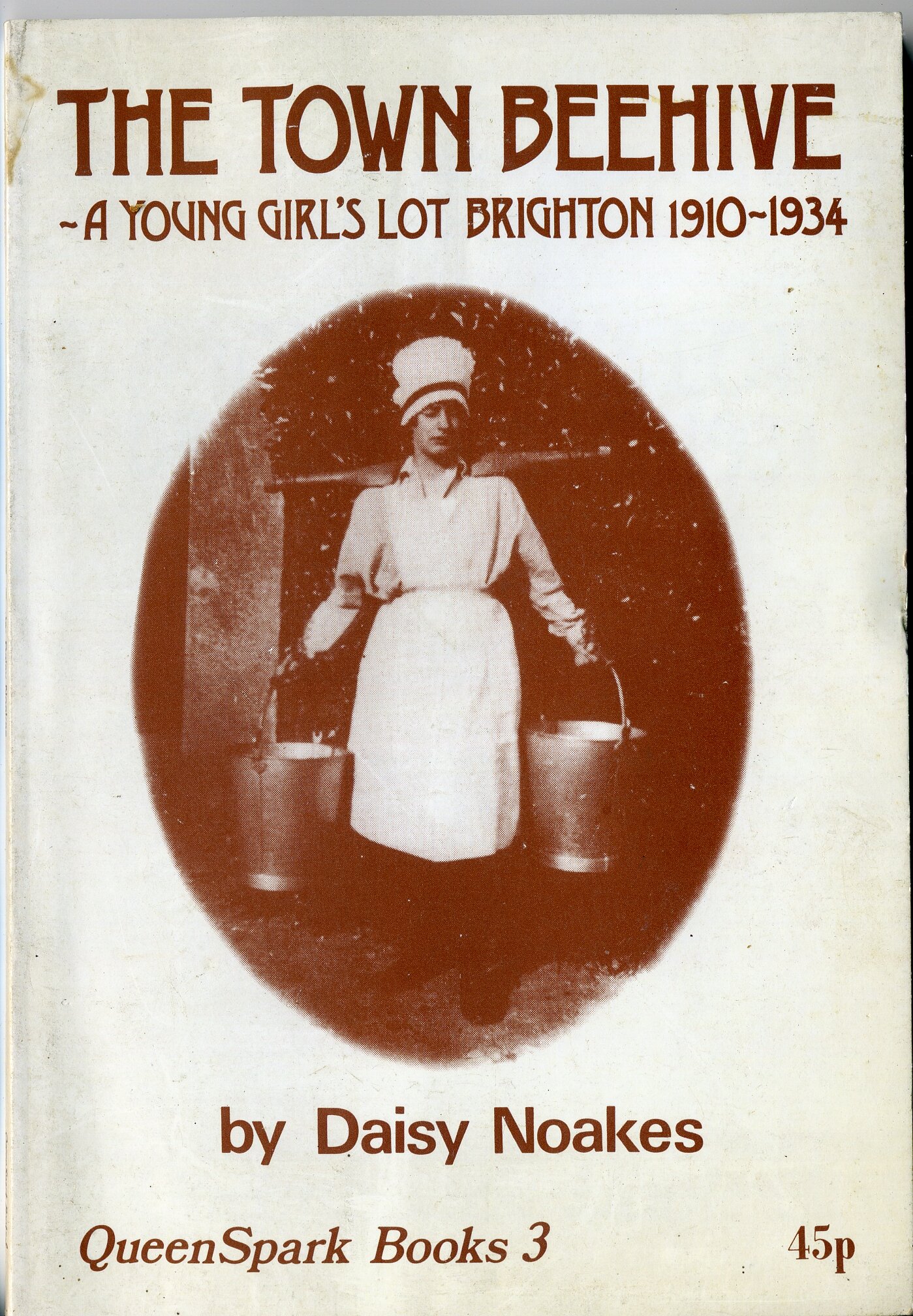

Robin loved working and interacting with a collective, where he became the natural animator. This is what happened with QueenSpark Books, a local association which, since 1972, has published dozens of autobiographies of men and women, almost all of them workers and artisans, living in the Queens Park area of Brighton. These life stories, illustrated with photographs, document in a lively and compassionate way the economic and social changes that these people and their community have gone through. Frances, Robin's wife, was both the soul and the mainstay of this association, which was affiliated with the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers. The success of QueenSpark Books depends largely on the fruitful collaboration between the person telling his or her life story and those who record and transcribe it — a form of weaving where the weft and the warp complement each other harmoniously. The team members, mostly historians, including Frances, Ursula Howard and Stephen Yeo, have succeeded in giving these stories all their natural freshness and depth.

Robin was also closely involved with the ‘QueenSpark’ newspaper, a street paper that was the neighbourhood’s voice on local issues. It was written mainly by locals and sold door to door. I regularly sold it in my street. Whenever I took an issue round, I was invited in for a cup of tea and a chat at nearly every house.

Another initiative in which Robin played a part was the Hanover Community Centre, where, for example, he ran collective cooking days. This was in a working-class district, where projects of this sort showed up not only the latent tensions between the working-class and the new intellectual worker population but also the ways they complemented each other. We were privileged to have this field of experience for political action.

In 1980, the QueenSpark team embarked on a book to challenge Thatcher's monetarist policy, which was attacking local public services through cuts in education, health and social services budgets as well as other services such as parks, the environment, transport, housing, museums and libraries. ‘Brighton on the Rocks, Monetarism and the Local State’, published in 1983, addressed the situation in three ways, using a statistical analysis, interviews with public service staff, and photographs of the lived experience of those working in and using public services. The book owes a great deal to Robin's highly detailed socio-economic analysis of spending and taxation in the local community of Brighton and East Sussex. ‘Brighton on the Rocks’ was a great success, especially in local communities facing similar problems. It was published by the ‘QueenSpark Books’ association, with a distribution of 10,000 copies.

And the photography? When I arrived in Brighton, Robin had introduced me to the philosopher Walter Benjamin’s analyses of photography and to the works of the John Berger/Jean Mohr duo, in which the dialogue between images and words achieves such depth of meaning. Another way of telling. I was so entranced by these discoveries that my colleagues appointed me project photographer. My first steps as a photographer. Bob Golby, a bus driver and union leader, invited me to accompany him for a day. The next day I took my first picture of him preparing a hearty breakfast in his kitchen and then photographed him throughout his day at work on his bus, finishing up at the pub in the evening. In the book, this day takes up a double page of 16 images labelled with the time they were taken. After this, I spent a lot of time in council homes that were completely run down, where families were finding ways to decorate each room, hiding the cracks with personal items: photographs, posters, children’s drawings, toys, stuffed animals, statuettes, etc. This photographic project immersed me in the human warmth of these interiors, in freezing cold houses riddled with damp. The walls of these dwellings spoke of dignity and poverty.

The NYS, a revolution in education in the Seychelles

In 1977, a socialist government under the aegis of France-Albert René took power in the Seychelles. One of his key projects was the establishment of a new education system, the National Youth Service (NYS). The idea behind the NYS was that it was young people who had to spearhead the transformation of society — a society that still bore many traces of slavery and colonial capitalism. To stop the country coming adrift, it was necessary to act as a matter of urgency, in particular by giving young people the opportunity to live and produce things together and to acquire the personal attributes appropriate for the values of a socialist society: an ability to cooperate, an understanding of equality, a respect for manual labour and Seychellois culture and a sense of initiative and responsibility. The school system at that time was very selective. The vast majority of pupils lost their places at school after eight years of very mediocre education, while the number of students in secondary education — belonging almost exclusively to the bourgeoisie — was extremely small.

In my capacity as a UNESCO consultant, I was asked by the President to make proposals for the development of a project addressing the key question of socialist transformation as expressed by the Seychelles People's Progressive Front. I returned to Brighton and contacted Robin, who was enthusiastic about this project. We wrote a first report ‘The seed of the new society’ (July 1980) outlining the organisational forms of youth villages. The report proposed an integration of the three spheres of daily life (domestic activities, production and recreation) incorporating seven currents: politics, economics, health, justice, security, training and information.

To implement this proposal, an experimental camp was organised by a highly motivated Seychelles team. Under Frances’s instruction, a group of young people produced a newspaper, ‘Vilaz Lazenes’, in three languages (Creole, French and English). Robin, who came to the Seychelles at the time, created an electric atmosphere in the camp. On the basis of this experience, the government set up a number of NYS villages, which hosted young people for a two-year period in the ninth and tenth years of their education. This organisation succeeded in ensuring that nearly all young people in the country, girls as well as boys, remained in education until the age of 16 — latterly, 17 — which radically democratised the access of working-class children to education.

A few months after the opening of the first village in 1981, the new education system reached cruising speed, integrating domestic activities, production and recreation with the seven currents that intersected with them. The education/training system itself was organised around a core curriculum (French, English and Maths) with seven blocks of activity: agriculture, livestock, fisheries, construction, health, culture and information, through each of which every young person worked. The disciplines (history, biology, physics etc.) were taught with specific examples drawn from the practice of production. In this way, the production of NYS radio station programmes was linked to physics projects and the photo lab of the newspaper ‘Vilaz Lazenes’ to chemistry projects.

This first village had 810 young volunteers, including 400 girls, divided into 18 clusters of a maximum of 48 students, with boys and girls living in separate clusters. The coordinator of each cluster, elected for one month, ensured the rotation and the proper functioning of the domestic groups and specialised teams (information, culture, sport, store, finances, production, health etc.). The life of the clusters turned out to be extremely stimulating. Many cultural activities came spontaneously to fruition there. These were places of continual independent learning, where young people gained a sense of community based on cooperative relationships.

The young people were consulted about the architecture of the first village in a survey conducted with the help of Hubert Murray (‘Design and Construction in the NYS’). Their views were taken into account in the construction of new NYS villages. On the basis of this survey, Hubert designed a functional and attractive resource centre that won the Seychelles Architecture Award.

In June 1981, Robin and I wrote a new report, ‘The NYS and the wider society: from the seed to the flower’, analysing the relationship between the NYS and the divisions of society in the Seychelles. It has three chapters, each addressing a strategic issue:

-The capitalist knowledge economy

-Towards a new form of exams

-The NYS and the cooperative economy

The following year, we wrote a third report, ‘One year later’, describing ways in which the system had changed in some areas, compared to the initial plan. Thus, the village’s agricultural activity, initially organised along the lines of Soviet sovkhozy, was quickly restructured to combat low productivity, with each cluster (or group of about thirty young people) being made responsible for a piece of land allotted to it. This move from a statist to a cooperative model proved very fruitful.

We also noted a positive change in the representation of girls in village leadership positions. Observing that very few girls were elected to this level of responsibility, the NYS leadership put in place a system of parity that delivered very good results, with girls making it a point of honour to carry out their roles to the best of their ability. This reform benefited society as a whole, for many girls who had held positions in the NYS were later elected to various positions in the Seychelles political system and became key players in the country.

The NYS was able to mobilise high-quality human resources, starting with a team of seven coordinators from the Seychelles under the direction of Florence Benstrong: Bernard Shamlaye for Education, Olsen Vidot for Production, Eric Arnephy for Entertainment, Noëlla Antat for Interior and Exterior Relations, Julita César for Health, Benjamine Socrate for Administration and the UK consultant Simon Murray (Henderson). The 22 facilitators (13 men and 9 women) enjoyed both theoretical and practical training. At the end of March 1981, the team included teachers of the following nationalities: 8 from the Seychelles, 6 Guineans, 3 Mauritians, 6 Britons, 12 Canadians, 3 Sri Lankans and one Belgian.

During its launch period, the NYS brought in consultants for short-term assignments, with optimal results. These people, contracted because of their competence in specific areas and their openness of mind, agreed to donate their time because of their enthusiasm for this project. The following people supported the project in this way:

Frances Murray, the prime mover of the Friends' Centre and the QueenSpark community newspaper in Brighton. In the experimental camp of August 1980, she breathed life into the information project and trained facilitators and young people in the production of a newspaper, which was in three languages: Creole, English and French. Inspired by her encouragement, the young people wrote, edited and published three issues of the newspaper ‘Vilaz Lazenes’.

Nguyen Huu Dong, a sociologist and economist teaching at the universities of Nanterre, Hanoi and Algiers. He helped to train the facilitators and develop a method for planning production for the village and the clusters.

Colin Lacey, Professor of Education Science at the University of Sussex, Brighton. Working closely with the assistant coordinator for education, he helped design a process of transition from the school system to the new NYS education programme and prepared teachers for this transition period. He was also involved in the preparation of a curriculum development and evaluation method and the search for an alternative to Cambridge exams (O and A levels).

Jean-Michel Carré, founder of Grain de Sable Films and film director. He presented screenings of eight films for the young people, facilitators and teachers, including ‘Histoire de ballon’ (The Football Incident), ‘Une journée à Summerhill’ (A day at Summerhill), ‘Sucre Amer’ (Bitter Sugar) and ‘Alertez les bébés’ (Warn the babies). He also facilitated study sessions for teachers on the methodology of educational projects. Unfortunately, the film he planned to make could not be completed.

Kamoji Wachiira, ecologist, professor at Kenyatta University College in Nairobi, set up a hydroponic crop production project that was run by a group of students in the form of a club.

This wonderful project lasted 17 years, and from the seeds planted by Robin and the many who played a part and made individual contributions to the NYS has sprung a harvest of beautiful — indeed immortal — flowers.

KODAK

In 1982, after working for three years in the Seychelles, I was offered a job in France, in the communication and audio-visual sector of the Val de Marne Department, in the Paris region. The process of decentralisation was underway, and the Departments were beginning to sort out how their new responsibilities would be organised. The majority of those running the Department of Val de Marne were Communists and Socialists, headed by a Communist elected representative. Employment was a major concern of this Department, which was affected in the same way as the entire Parisian belt by the decline of industrial jobs. The idea was to make the most of local assets by bringing all possible synergies into play, in a sector-based approach.

I became aware of the serious crisis faced by the KODAK Pathé factory in Vincennes, whose workforce had shrunk from 3,000 to 2,000 employees in less than 10 years. The factory produced photographic material for photography and the cinema. In a direct attack on its major industrial, scientific and technological potential, the Directorate had just announced that the plant and its high-performance research centre would close in 1987.

Knowing that there was a large Kodak factory in Harrow in Greater London, I contacted Robin, who at the time was Director of the Department of Industry and Employment at the GLC (Greater London Council). We immediately saw that there would be important opportunities for the two local authorities to take joint action. Thus began a wonderful story of rapprochements between not only these two local authorities on either side of the Channel and all the unions of their two factories, but also other sites in Europe — bringing together executives, researchers and labourers of the United Kingdom, France, Belgium and Italy.

First, elected officials and technicians from the Val de Marne visited London with representatives of the factory unions and the Vincennes research centre; then Robin went to Vincennes accompanied by GLC technicians and union representatives from the Harrow factory and research centre. On the occasion of this visit, the GLC and the General Council of the Department of Val de Marne agreed to carry out a joint work of study and research on both the subsidiary Kodak Ltd, with the Harrow factory and research centre, and the Kodak Pathé subsidiary with the Vincennes factory and research centre.

In June 1983, in cooperation with the Greater London Council, represented by Michael Ward and Robin, the General Council of Val de Marne organised a ‘Study and Information Day’ attended by representatives of all unions within Kodak Ltd and of those from five French Kodak Pathé sites: Vincennes, Châlon-sur-Saône, Sevran, Marseille and the Paris headquarters.

Thanks to this rapprochement and the opportunity to exchange information, trade unionists from both countries were able to understand better Kodak’s plans for restructuring in the UK and in France. The first stage that the firm had in view was a relocation of some activities to another national site (Nottinghamshire instead of Harrow, Châlon-sur-Saône in place of Vincennes), involving considerable job cuts, and banking on the rivalry between a strongly unionised workforce in urban centres and one with a less embedded union tradition in rural areas. Through the opportunity to meet and talk with their European counterparts, employees also came to realise that the research and development activities of Harrow and Vincennes were to be transferred entirely to the Rochester headquarters in the United States. The researchers and technicians at these two research centres saw that the work they were doing designing new photographic products was being blocked and doomed to failure by the firm’s international management strategy.

It was clear to the unions that the British company Kodak Ltd and the French company Kodak Pathé had to all intents and purposes ceased to exist and that decisions about them were being made at a much broader level, both European and global. The management of both companies, however, denied this. Faced with this situation, the French and British unions who had gathered in Vincennes decided to work together. They created a joint organisation with its own journal, ‘Viewfinder’. The Italian and Belgian unions joined in and the newspaper KODAK EUROPE was then written in English and French.

It was in this context that I met Claire Prost, who held the Kodak brief in the Val de Marne Department. Together, we supported the Kodak unions through this process of European cooperation. Our pooling of resources worked so well that we later decided to live together! (Clic Clac Kodak). In 1985, Claire, who joined me in London, went on with this support work in the GLC Industry and Employment Branch, under Robin’s direction.

Several conferences were organised in England, France and Italy, focusing on the need for unity at a European level — including between unions and management — against the parent company Eastman Kodak in the United States, in order to protect research and development and invest in new products in Europe. Trade union leaders called for direct negotiations with the European management in order to keep in Europe the collective know-how accumulated over the years and its potential for innovation. The GLC funded the union newspaper, which was sent in thousands of copies from London's Victoria Station to union headquarters across Europe. The GLC and the General Council of Val de Marne supported the Kodak unions with the European Commission and the European Parliament.

This Kodak initiative, undertaken with determination by two local authorities from two European countries together with the trade unions of several European countries, is in more than one way a textbook example. It was brought to an abrupt stop when the GLC was abolished. On the face of it, the balance of power might appear to have worked in favour of the multinational, and in line with its strategy, since most of Kodak's European activities came to an end. Yet Eastman Kodak soon went bankrupt, plunging the city of Rochester into misery. Kodak's strategic error was to destroy ‘the collective worker’ in its two European research centres. This prevented it positioning itself with new products, especially in the digital sphere.

TWIN and TWIN Trading

The Greater London Council (GLC), a community of 7 million people, was, before its dissolution by the Thatcher government in 1986, an example of a socialist strategy that was an alternative to the Keynesian social democratic policies which European left-wing parties automatically adopted as soon as they came to power. A socialist alternative to Margaret Thatcher's slogan, ‘There is no alternative’. It was from this perspective that the GLC, under Robin Murray’s leadership, developed an industrial strategy that put restructuring in the interest of workers before capitalist rationalisation. Every day, the GLC hung out on its façade, opposite Mrs Thatcher’s office on the other side of the Thames, a huge banner showing the number of the unemployed.

From the end of 1983 to ’86, I worked closely with Robin and Michael Barratt Brown to design and implement a system of cooperation between the GLC and the Third World to create sustainable jobs and to improve the quality of work and the living conditions of producers.

It was in this context that the GLC financed the creation of two organisations: TWIN (Third World Information Network), an NGO with charitable status, responsible for research, information and education on trade and technology, and TWIN TRADING, a charitable company limited by guarantee — which means that, although it can carry out commercial activities for profit, it may not distribute the profit to shareholders but must invest it in its own activities. As a key member of the Advisory Board of both organisations, Robin played a strategic role from the start.

The mission of these organisations is to develop new forms of economic relations between the South and the North or, more precisely, between progressive organisations of the Third World and the First World: non-exploitative relations based on the mutual benefit of both parties and their independence. As Robin's work has shown, relationships between South and North, which are currently controlled by multinationals, cause economic, social and environmental damage in both worlds. The organisation of an alternative to the current dominant system of trade and technology transfer is therefore imperative.

The idea is to create opportunities for Third World producers to supply European consumers with high quality products at relatively low prices, while allowing them to keep a maximum share of the value they create. To do this, it is necessary to mobilise not only provision for training, research and development but also resources to support the production of technologies appropriate to the needs of Third World producers.

In February 1985, with the technical support of Twin Trading, the GLC organised an international conference, Third World Trade and Technology Conference, bringing together representatives of 22 African, Asian, Latin American and Caribbean nations with those of several European countries and many participants from Great Britain. Most of the participants were development specialists invited to become partners of TWIN and TWIN Trading.

In the immediate aftermath, we worked with one of them, Mazid Ndiaye, president of the NGO RADI (Réseau Africain pour le Développement Intégré - African Network for Integral Development), to develop a ‘Support project for the development of off-season crops in three villages in the region of Mbour in Senegal’, financed by the European Union. TWIN helped farmers' associations in these three villages to adopt adapted irrigation technology, which allowed them to supply fresh vegetables to hotels in this tourist region for several years. It was a form of fair trade in miniature, with small local producers supplying these commodities to foreign tourists at a fair price, thanks to the long-term perspective of the operation.

TWIN and TWIN Trading were active mainly in two fields of activity:

a) the production and exchange of socially useful technologies. We benefited here from the resources of the Greater London Enterprise Board (GLEB – now Greater London Enterprise Ltd (GLE)) and its technological networks (Energy, Textile, Transport, Information and Communication Technologies). These networks, set up by the GLC under Robin’s enlightened and enthusiastic leadership, enable co-operation between companies, universities, polytechnic institutes, research departments and individual researchers with a view to focusing on new goods and services that could be produced by companies in London or the Third World. The basic principle was to start with the specific needs of Third World organisations in sectors where TWIN Trading could provide technical and economic expertise.

The following three projects were run in the first year:

We established a partnership between a timber company in Mozambique and a small furniture business in London, the former providing the cut wood to the latter for the manufacture of its beds. In Vietnam, we helped a state-owned tinned pineapple company to identify technology appropriate for its size and raw material supply capacity. Using a barter system, we provided computers to an organisation in Nicaragua in exchange for handcrafts, including rocking chairs and cigars.

(b) Trade between small producers in the South and consumers in the North. If the chain of intermediaries between producers and consumers is eliminated, the former can obtain better remuneration for their work. This is the principle of fair trade, that also relies on the solidarity of consumers in the North. TWIN Trading, however, goes further by establishing a direct link between producers and consumers, allowing consumers to influence the production and marketing process through the cooperatives. These consumer organisations gave producer organisations their opinion on the taste of coffee, chocolate and nuts as well as on their packaging and even their brand names, such as ‘Divine’ chocolate, ‘Liberation’ nuts and ‘Cafédirect’. Robin advocated enthusiastically for these designations.

We started by importing coffee made by small producer organisations in Nicaragua, roasting it and marketing it through sympathetic groups such as student associations and trade unions. TWIN and TWIN Trading currently have about 25 competent and motivated employees, who work with 43 organisations representing 300,000 small producers of coffee, cocoa and nuts from Africa, Asia and Latin America. These products are sold in supermarkets. At the head of the Advisory Board of TWIN and TWIN Trading for nearly 30 years, Robin played a key role in ensuring that the social, political and economic principles underpinning this project were properly applied.

The three Hs: Head, Heart and Hand

Robin liked to say that one had to act with ‘the three Hs’: the head, the heart and the hand. He embodied this trilogy.

First, the head. A highly cultivated man, of luminous intelligence, he had an independent spirit of tremendous creativity. In the many training sessions and lectures he gave, Robin stimulated the intellects of generations of students and participants. He imbued the projects he led with theoretical reflections that made them a field of fertile experimentation.

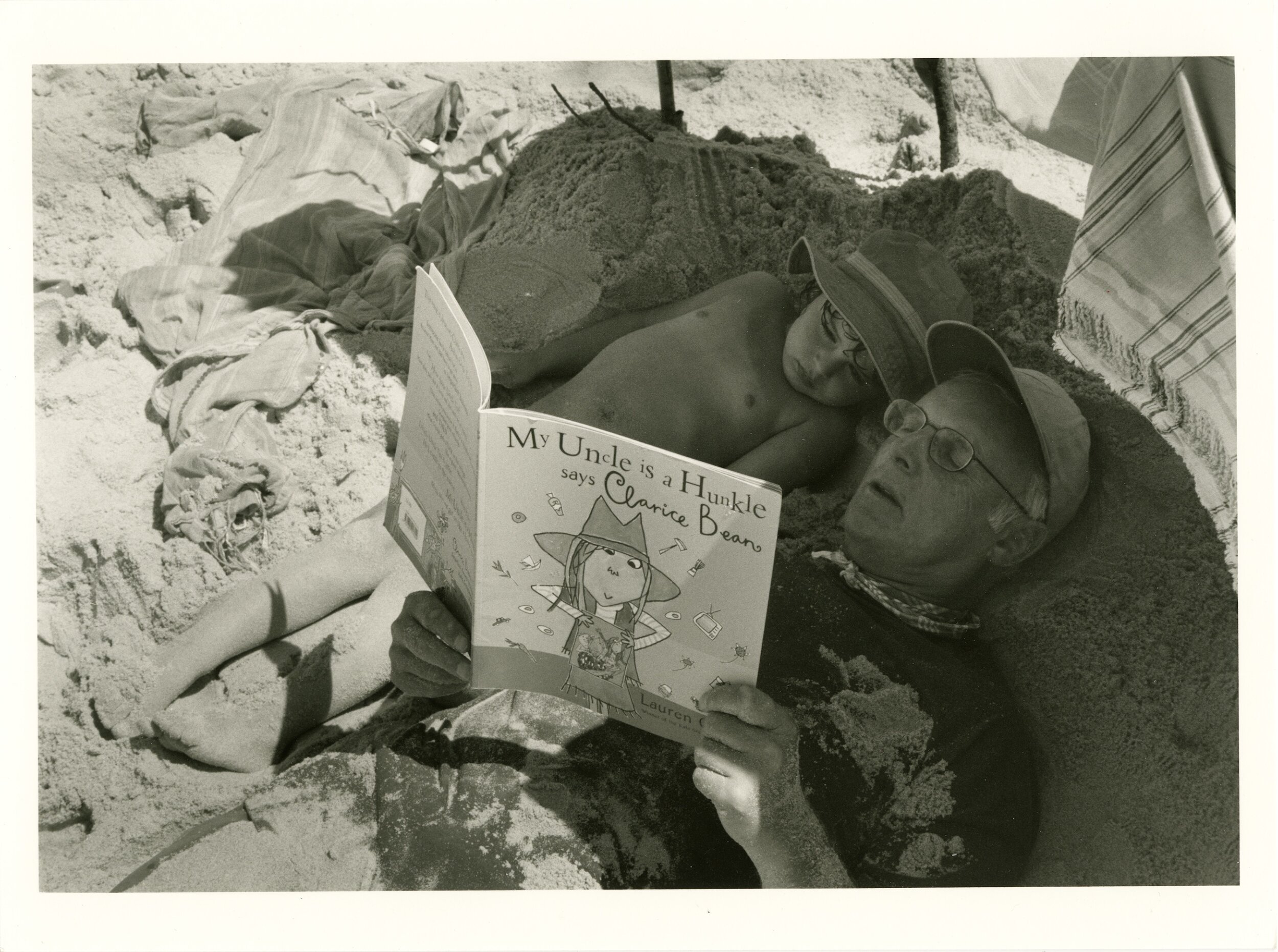

At the same time, the heart. Robin's brain beat in time with his heart. He was always passionate about people and about what he could do with others. He breathed gaiety and shared it with you. Hence his charisma and his ability to persuade people to pool their energies in the projects he led. He multiplied himself for his family and friends. He listened and debated with passion. There were so many discussions where we stopped short in every possible space, when an exchange was at its most intense — out on the Downs, on Cumberland roads, on the snow-covered paths of the Fagnes in Southern Belgium, in the trails of the Seychelles islands, in the Murs à Pêches orchard in Montreuil, in the middle of Lake Okanagan or Sugar Lake, or in the channels of the Bassin d'Arcachon — before resuming our walk .... From the moment I started to take photography seriously, Robin became my best viewer and commentator.

And of course, the hand. Robin pitched in with the most menial tasks, just as he put his hand to the wheel on the spot for the causes he fought for. His theoretical reflection was nourished by his practice. Rather than pursue a university career that gave him security, he preferred to focus his energy on direct economic, social and environmental innovation.

Robin greatly admired William Morris, who had an intense commitment to his socialist convictions and his vision of the beauty he wanted to restore to all. When William Morris died in 1896, his doctor said that he had done the work of ten men in his lifetime. How many Robins can we tally up today?

Political economy

For Robin, socialism made sense only if it was at once economic, ecological and social. He was very critical of the old, ‘statist’ conception of socialism. He showed with The London Industrial Strategy of the GLC and with other initiatives how an economy was above all a question of relationships of production rather than of distribution. He also highlighted the key role played by a social and solidarity economy in an economic and social development strategy and showed how much more important this role had the potential to be. Ultimately, he thought that economics and ecology had to be closely linked and mutually reinforcing. He sometimes gave the impression of being idealistic or utopian, but he had the gift of bringing the most beautiful economic and ecological utopias to life.

A few days before his death, he explained to me that the book that had most transformed his life was Marx’s ‘Capital’, which he had read with passion on his arrival at the University of Sussex in a Capital reading group. He freed this Marxism from its dogmatic weight, giving it, with a joyous eclecticism, a human face where the dream becomes reality.

In those last days, Frances, Beth, and I heard him explain haltingly to an imaginary audience, in a fragmentary way, the contents of a book that would be his testament. A book on the evolution of capitalism, focusing on the history of money from third millennium Mesopotamia onwards. A book that seemed perfectly structured in his head. At the time when I had to leave — it was very late — he was announcing a chapter on the contradiction between capitalism and democracy.

Poetry

Robin linked ‘the three Hs’ through his sense of poetry. It was his true passion. He enjoyed making calendars with a carefully chosen poem for each month. His 2008 calendar, ‘A Calendar of Water Poems’, inspired my photographic work ‘Hymne à l'eau’ (Hymn to Water). This calendar opens in January with Alice Oswald's ‘Sea poem’:

‘what is water in the eyes of water

loose inquisitive fragile anxious

a wave, a winged form

splitting up into sharp glances ...’

and closes in December with ‘Snow and Snow’ by Ted Hughes:

‘Snow is sometimes a she, a soft one.

Her kiss on your cheek, her finger on your sleeve

In early December, on a warm evening,

And you turn to meet her, saying 'It is snowing!'

But it is not. And nobody's there.

Empty and calm is the air.’ ...

I was very happy to be able to spend a few days with Robin before he died. He found it very hard to breathe. His love of poetry helped him a lot. I took over from Mika and Beth, who were reading him poems. The music of poetry delighted him to the point of quieting his breathing. I, in my turn, had the joy of reciting for him some poems that I love and which he listened to with great attention. I have chosen some excerpts:

‘Recueillement’ (Meditation) by Charles Baudelaire:

‘Sois sage ô ma Douleur et tiens toi plus tranquille.

Tu réclamais le Soir, il descend, le voici:

Une atmosphère obscure enveloppe la ville,

Aux uns portant la paix, aux autres le souci.’ ...

(Be good, O my Sorrow, and keep more calm.

You longed for Evening; it is falling; now:

A dusky atmosphere enfolds the town,

Bringing peace to some, to others care.)

(translation © Richard Stokes, from A French Song Companion (Oxford, 2000))

‘Sensation’ by Arthur Rimbaud :

... ‘Je ne parlerai pas, je ne penserai rien :

Mais l'amour infini me montera dans l'âme,

Et j'irai loin, bien loin, comme un bohémien,

Par la nature, - heureux comme avec une femme.’ ...

(I shall not speak, I shall think about nothing:

But endless love will mount in my soul;

And I shall travel far, very far, like a gipsy,

Through the countryside - as happy as if I were with a woman.)

(translation © Oliver Bernard: Arthur Rimbaud, Collected Poems (1962))

‘La Chanson du Mal-aimé’ (The Song of the Badly-loved) by Guillaume Apollinaire:

… ‘Mon beau navire ô ma mémoire

Avons-nous assez navigué

Dans une onde mauvaise à boire

Avons-nous assez divagué

De la belle aube au triste soir’ ...

(My handsome ship O memory mine

Have we had our fill of sailing

Through a sea of gall and brine

Have we had our fill of trailing

From the fair dawn till sad moonshine)

‘Marie’ also by Guillaume Apollinaire:

… ‘Les masques sont silencieux

Et la musique est si lointaine

Qu'elle semble venir des cieux

Oui je veux vous aimer mais vous aimer à peine

Et mon mal est délicieux’ ...

(The masquerades are still again

And the music far and low

Seems a heavenly refrain

Yes, I yearn to love you, but only hardly so

And I revel in my pain)

‘Brise marine’ (Sea breeze) by Stéphane Mallarmé:

‘La chair est triste, hélas ! Et j'ai lu tous les livres

Fuir ! Là bas fuir ! Je sens que des oiseaux sont ivres

D'être parmi l'écume inconnue et les cieux !’ ...

(The flesh is sad — and I’ve read every book.

O to escape — to get away! Birds look

as though they’re drunk for unknown spray and skies.)

(Translation E. H. and A. M. Blackmore, Oxford World’s Classics)

I can still hear Robin reciting ‘The leaden echo and the golden echo’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins:

‘How to keep – is there any, any, is there none such, nowhere known some, bow or

brooch or braid or brace, lace, latch or catch or key to keep.

Back beauty, keep it, beauty, beauty, beauty...from vanishing away ?’ …

The answer to the poem’s question is in the ‘golden echo’ of which Robin had his own vision. We measure the difference a project has made by the golden echo that rings on, an echo that makes a mockery of death. Robin or the beauty of life.

November 2017

Montage of the photographic essay by Gaël Delpech

Translation: Abigail Graham 2019